HOW TO

Get the most out of our sessions.

What you do between our sessions is just as important as the calls themselves. Let's discuss the best way to use our sessions.

The key to improving your English is what you do between our sessions. During our sessions you'll likely get a lot of information, grammar tips, new vocabulary, or just new ideas for how to use English. If you're going to use these to improve then you need to find a way to integrate this new knowledge into your active, working, English. That's the English that you use every day. We're going to start by discussing specifically how to make sure that you're improving consistently between our sessions and then we'll move onto a little psychology related to why this technique works. If you'd like to see all of this information in a youtube video instead, feel free to click here to be taken to a video I made on this topic.

First, choose a specific thing from our session that you would like to improve. This could be a piece of vocabulary, a grammar point, a sentence structure, or really anything else. The key here is to get specific. The more specific you're able to get, the easier it will be to improve.

Second, get some practice with it. There are three stages to practicing a piece of English in real life.

Before an English interaction.

Remind yourself of the specific piece of English that you're working on. Remember, be as specific as you can. Looking for opportunities to use a specific word or phrase is perfect.

During an English interaction.

Look for opportunities to use your practice point. Try to use your target vocabulary or grammar more than you usually would. The more times you can use it, the more you will improve your ability to use it.

After an English interaction.

Review what happened. There are two questions that are useful here. Did you use it correctly whenever you had the chance to? Did you miss any opportunities to use it? Doing this little review with yourself after each English language interaction can really accelerate your improvement.

So why doe this method work? Why does it make sense to find these specific, small, opportunities. Maybe you feel like you've only made a 1% improvement this week. In fact, that 1% improvement is the goal. Most of the people I work with can speak English. You can already communicate to a pretty good level. However, what we're looking for is that last 10 or 20 percent that separates you from a native speaker. These are the little 1% ideas that we're looking for.

If you want to make this a little easier, try the coffee card method. This is a tool that a lot of the international professionals I work with have found to be really useful.

I've made a YouTube video explaining it in detail and you can click here to see it.

Just five years after Brailsford took over, the British Cycling team won 60% of the gold medals for cycling at the Beijing Olympic games. Four years later, when the Olympic Games came to London, the tean set nine Olympic records and seven world records. The also won the world's most famous and difficult cycling race, the Tour de France, in 5 out of the next 6 years.

I think about English communication coaching in the same way the British Cycling team thought about their goals. We're looking for specific, 1% improvements, that we can focus on and actively practice and apply to the way you use English.

Brailsford and his coaches began by making small adjustments you might expect from a professional cycling team. They redesigned the bike seats to make them more comfortable and rubbed alcohol on the tires for a better grip. But they didn’t stop there. They continued to find 1% improvements in overlooked and unexpected areas. They tested different types of massage gels to see which one led to the fastest muscle recovery. They hired a surgeon to teach each rider the best way to wash their hands to reduce the chances of catching a cold. They even determined the type of pillow and mattress that led to the best night’s sleep for each rider. All of these tiny changes culminated in some incredible results that arrived in a surprisingly short amount of time.

Lessons from the British Cycling team. In 2003 the British Cycling team was considered one of the worst in the world. Since 1908, British riders had won just a single gold medal at the Olympic Games. Even some top bike manufacturers refused to sell bikes to the team because they were afraid that it would hurt sales if other professionals saw the Brits using their gear. Eventually however, the team hired David Brailsford. David was famous for this philosophy of searching for a tiny margin of improvement in everything you do. “The whole principle came from the idea that if you broke down everything you could think of that goes into riding a bike, and then improve it by 1%, you will get a significant increase when you put them all together.”

A quick point regarding grammar. Using new vocabulary is relatively easy. Vocabulary is very specific. You just need to remember a new word and then start using it. However, grammar is a lot more difficult. Grammar rules need to be applied to lots of different sentences in lots of different contexts. So it might be quite easy to say, "OK, I'm going to use the word 'proactive' today", but really difficult to say, "OK, I'm going to use the present perfect progressive tense today. Our method here is again to get really specific. We'll look for common sentence fragments. Building blocks that you can use to start using these grammar rules and practicing with them. We'll also look for "trigger words". Words that, when you use them, you are very likely to need a particular grammar rule. For instance, the word 'since' often indicates that the sentence should be in a perfect tense.

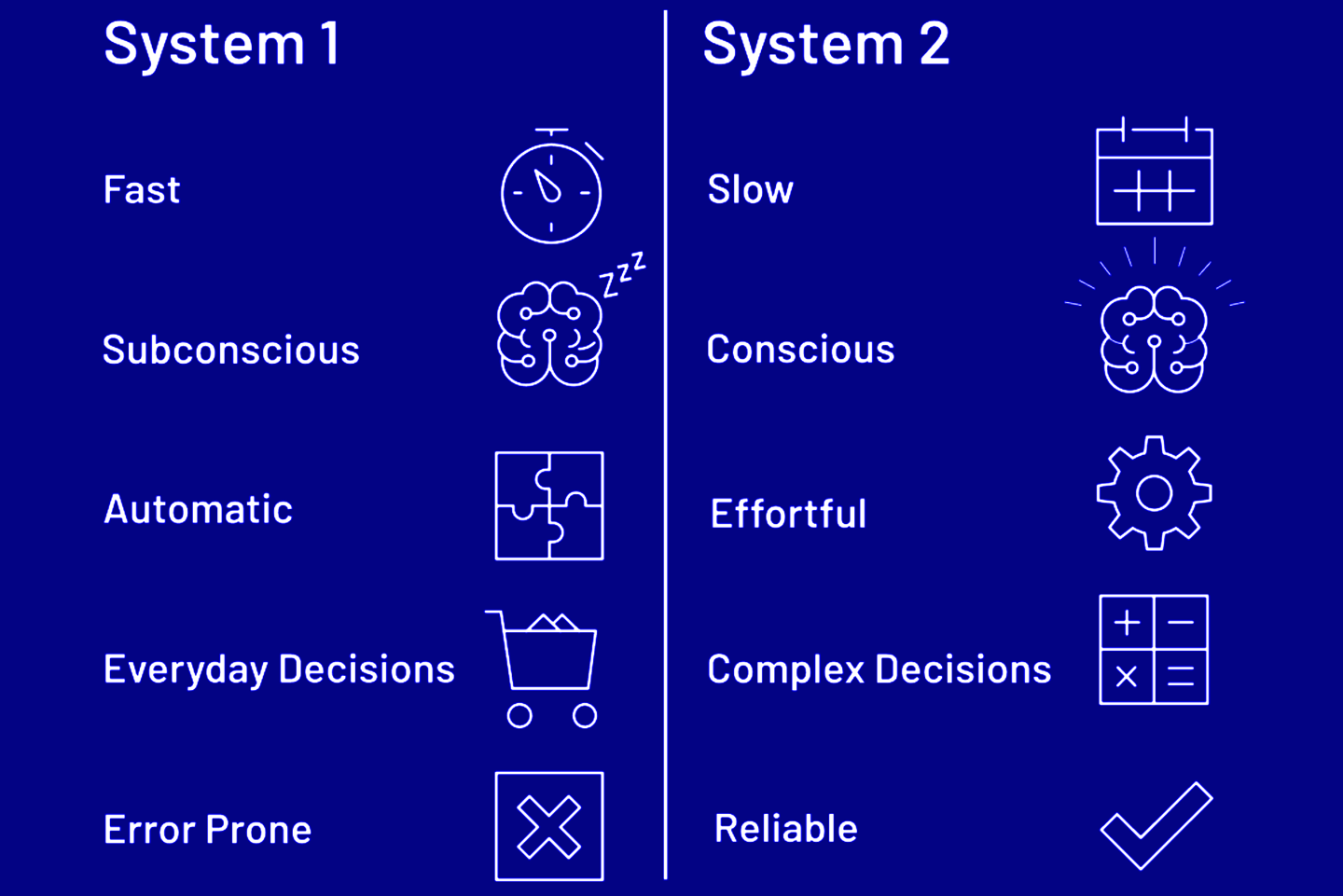

What we need to do is to move this knowledge from your system two thinking over to your system one thinking. If you're making mistakes when you're speaking, but not when you're taking your time and looking at a piece of writing then this information is available to your system one brain, but not your system two brain. Our task therefore is really simple. We need to move this information over and train your system one brain to use it. The best way to do this is through the three stage process that we've outlined above.

And of course, if you have any questions please feel free to ask me in our next session!